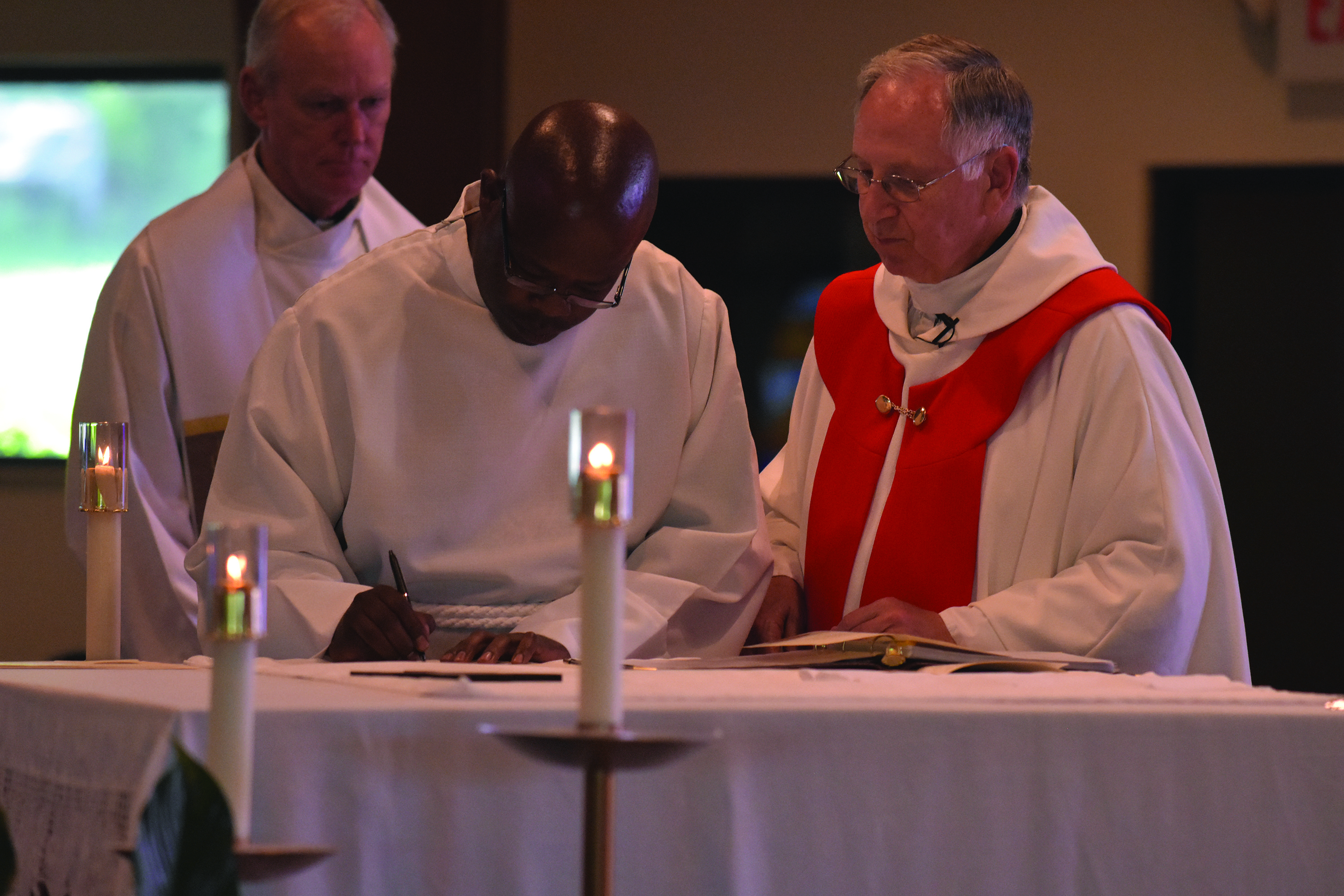

L to R: Volunteers John Potterton, Mary Carew, and sister-in-law Molly Carew lift a wall that will shelter a family. Photo by John Feister.

In the wake of a devastating flood, Glenmary volunteers reunite to help build a house.

When Wilma Combs drove up the mountain hollow in Breathitt County, Eastern Kentucky, on September 26, she must have taken a deep breath. Her prayers were being answered. A construction crew, joined by a group of older volunteers, was raising the walls of her new home. The volunteers this week were together for a working reunion of friends who first volunteered in Appalachia with Glenmary in the 1970s.

“We were trying to just figure out what we were going to do,” homeowner Wilma recalls. Her old home, like thousands in the region, was destroyed by historic flooding in July 2022. She, her husband, and four children have been through the wringer since then: “We’ve moved six times. It’s been rough. But God got us through this, every bit of the way.”

Providentially for the Combses, there was a nonprofit housing company in nearby Hazard that quickly grew in response to the crisis. The Housing Development Alliance helped the family to secure a government loan to buy flood-free land and arrange for construction of a new house. Then the Combses waited, as work around them started. And they began a new family ritual, says Wilma: “We come up here weekly and we pray.” This day, when they came, she saw God had brought volunteers to help.

Shelter the homeless, visit the sick

Each of the former Glenmary volunteers, now women and men in their 60s and 70s, could look back on how their volunteer work 50-some years ago helped to shape their lives of mercy in whatever home community they returned to.

Actually, Tom Carew and Molly Barrett never moved back home. Molly, a Minnesotan, came in 1971 to work among Franciscan sisters at Glenmary’s Holy Redeemer Parish in Lewis County. “I just was amazed at how much a different culture it was, how different it felt from the city of St. Paul, where I grew up.” She spent her career as a visiting nurse, then nurse practitioner, in nearby Rowan and Elliott counties, also once served by Glenmary.

Tom, from New York City (Queens), came to rural Lewis County in 1971 with a group from Fairfield University. “I met [Glenmary] Brother Bob, then Brother Ralph and helped a family get a house in Vanceburg.” He then stayed to manage Glenmary’s new volunteer program at a remote place that came to be known as The Farm. Tom was the first farm manager in a program that has since brought 20,000+ volunteers to Appalachia. “I was so influenced by that, that I wanted to continue some form of ministry,” he recalls. He was also influenced down the hills in Vanceburg by Molly, now his wife of 45 years!

Tom moved to Rowan County, site of Glenmary’s Jesus Our Savior Parish. There, he and Glenmary pastor Father John Garvey organized local ministers to help found a nonprofit affordable-housing company, Frontier Housing. While Molly was learning nursing in the US Navy, in faraway Virginia, Tom gathered a crew and started building houses. “I quickly realized if we didn’t figure out the money side of things we wouldn’t be doing this for long.” Glenmary pitched in about $10,000, and then others joined, as Tom recruited more and more. Then Molly returned, they married, and settled in Morehead. Molly found work in St. Clare Hospital, itself a Notre Dame Sisters’ mission effort to bring improved health care to an underserved area. Over the years, they raised four children.

While Molly was tending to the sick across the county, Tom was helping families get their first homes, hundreds as the company grew. Then Tom became a consultant to other nonprofit affordable-housing efforts across Appalachia, and served as principal author of a federal policy that would enable nonprofit housing providers across the United States to help working low-income families receive US Department of Agriculture (USDA) housing loans. He served as president of the National Housing Coalition. He was recently called out of retirement to lead Kentucky’s statewide USDA Rural Development program.

“My whole adult life was influenced by Glenmary,” Tom says. “And I’m an old man now, so that’s a long time!”

Instruct the ignorant, feed the hungry

As a young woman, Annie Finn wasn’t sure she could survive elementary teaching in Boston (Dorchester). Her principal suggested she take a year off. “That turned out to be a great gift,” she says. She came to Holy Redeemer Parish in Lewis County as a volunteer in the early 1970s.

Founding pastor Glenmary Father Pat O’Donnell, who welcomed a constant flow of volunteers and Catholic sisters, sent her to a local school to get a job. He wanted to break down Catholic stereotypes with this pleasant, well-spoken young woman, licensed to teach. “It was an awkward interview,” she recalls, laughing about her talk with a Lewis County administrator. Here was an outsider, a Catholic, looking to work in his school. “The guy was looking at me like I had horns in there, under my hair! He wanted to know, ‘Would you be wearing that garb?’” He meant a sister’s full habit, a strange thing he had seen in photos from elsewhere. She didn’t get the job.

Many years later she wrote a thank-you letter to Father O’Donnell, as she still calls him (he was Father Pat to most): “I thanked him. The experience so enriched my life. I thought he should know that he had done that for me and for so many other people. And he sent me back a very nice letter, which I was touched by. He also put in a donation envelope!”

After she returned to Boston, she indeed taught children, and eventually became a hospital chaplain.

Comfort the afflicted

Chuck Garvin looked like a likely vocational recruit to Father Pat when he came to spend a year at Holy Redeemer in Vanceburg. It didn’t turn out that way; he went on to become a doctor back home in Cleveland, Ohio, known for his community service. Even today, post-retirement, he is helping stabilize the work of an inner-city clinic that serves many people living in poverty.

He credits his Glenmary experience, in part, for his learning how to serve: “It’s a less arrogant kind of service. It’s generally humble, a compassionate accompanying of people rather than just a handout. It’s more of a presence. It’s an awareness that we all have differences, but we all need each other. We are poor in different ways, and rich in different ways. Glenmary helps to nourish that sort of understanding.

“I tried to not be a very paternalistic doctor, either. I didn’t only look for what is wrong with people. I feel like on my better days I included with that, ‘What’s right, and how can we build on that.’”

He also spent a week a year for two decades going to serve the poor in Honduras, and repeatedly went to provide medical relief after natural disasters, such as Hurricane Katrina.

Each of these is one of 20,000 stories of lives exposed by Glenmary to a reality far from home. That story continues even today, as the volunteer program, now at Joppa Mountain, Tennessee, will host about 300 volunteers this year from places far from Tennessee.

For those who stayed, like Molly Carew, “it turned into something really, really wonderful, forever!” She and her fellow nurses covered five counties, seeing maybe seven to ten people daily, “surely more than a thousand over years,” she says. “Glenmary’s impact here has been huge.”

That spirit of service that Glenmary nurtured in Molly, Tom, Anne, Chuck, and thousands of former volunteers, including this writer, continues to ripple. Lives are still changing for the better within the territory Glenmary has served—and beyond.

– John Feister

This story first appeared in the Winter 2023 publication of the Glenmary Challenge.