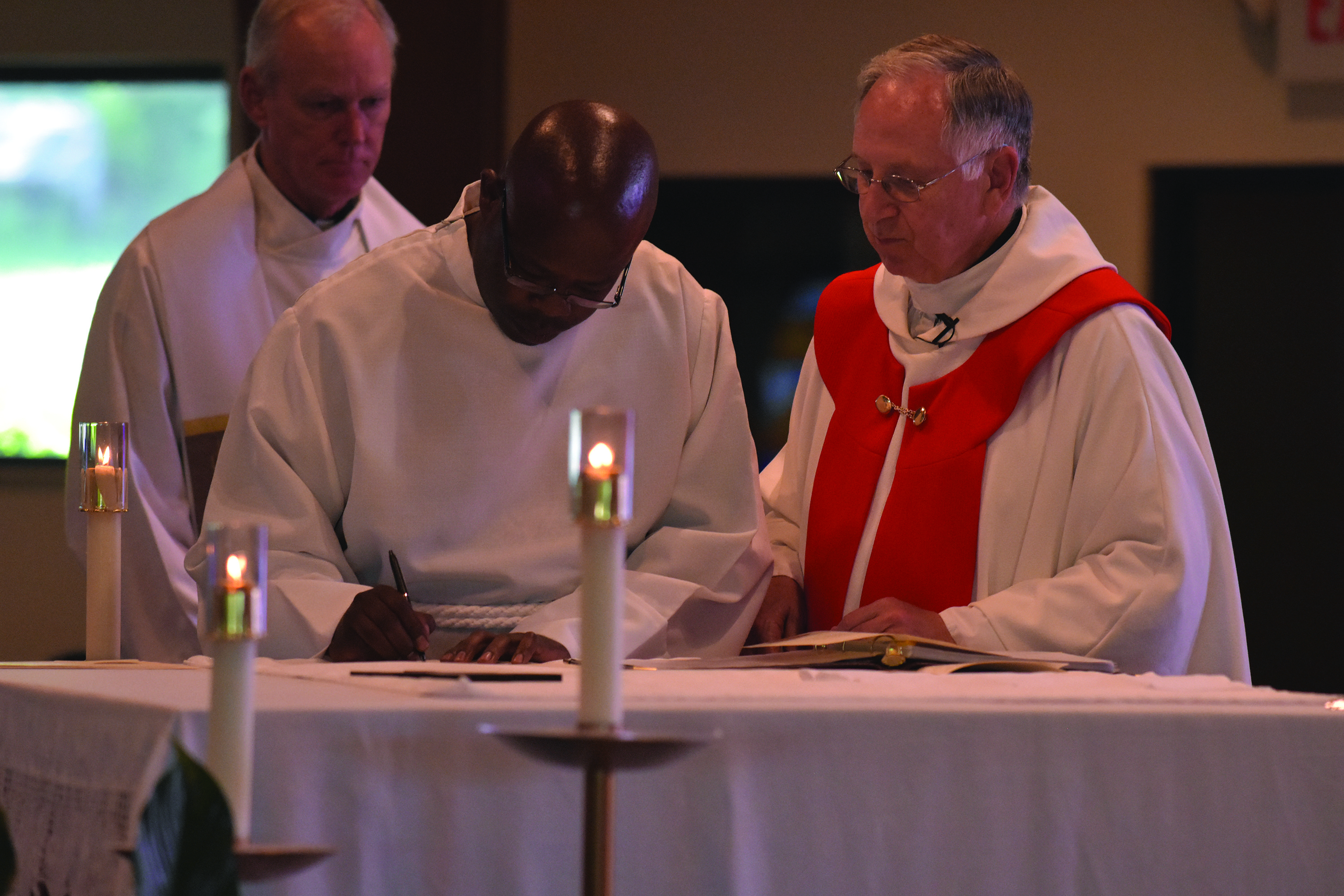

Glenmary students at Xavier University of Louisiana (L to R): Cavine Okello, Jude Smith, Joseph Maundu, and Fredrick Ochieng’.

Four Glenmary students immersed themselves in Black Catholic culture last summer. Here’s what they learned.

“I was amazed how little I knew about the Black experience in the United States!” That’s Glenmary seminarian Fredrick Ochieng’, describing his experience this past summer at the Institute for Black Catholic Studies (IBCS) at Xavier University of Louisiana. Four Glenmary students, Fredrick along with Joseph Maundu, Cavine Okello, and Jude Smith attended a 7-week session at the Institute to learn more about African American culture and its expression in Christianity, in Catholicism.

Frederick found it to be an educational boost, helping him to, in his words, to “feel inspired, well-informed and ready to work and minister to the specific needs of African Americans, especially in our missions (like Blakely, Georgia, and Plymouth, North Carolina).”

Glenmarians often work across cultures. Northerners join Glenmary and come to the Deep South, where all sorts of casual things a Minnesotan or Chicagoan might say cause misunderstanding. New Yorkers might talk too fast for southern Applachians.

Truthfully, we all encounter these cultural divides even in our hometowns. Glenmary is devoted to bridging cultural divides.

Dr. Cecilia Moore is on the summer faculty, teaching the history of US Black Catholics (there are three million), and explains that the Institute started at Xavier in 1980. They offer graduate studies (a master’s program) and the continuing education program that the Glenmarians attended. That program includes history, theology, music, liturgy, and art, she explains. “We think one of the benefits is that the Glenmary students will be ministering in rural and southern communities. It will be to have a good sense of African American history and spirituality, and a theological perspective.” Dr. Moore, like the rest of the IBCS faculty, is herself African American. She is a professor at the Marianist-run University of Dayton.

Joseph Maundu says that, learning what he learned, “I awaken the spirit of community life in me. I will increase the spirit of collaboration in my ministry.” He says that he will “employ the African spirit of communion in the ministry.” That’s a piece of the cultures of Africa that has persisted in the American Black community, especially at Church, despite all of the intentional cultural destruction that was part of slavery. (For example, enslaved Africans of the same language group were intentionally separated from one another as a method of control.)

The days at the Institute are marked by a combination of college class and cultural experiences. “This is an opportunity for them to see and to participate,” explains Dr. Moore. There is morning praise, in the style of Black Catholic culture, that the students help to prepare. There is daily Mass at noon. “On Tuesday and Thursday nights, there’s African dance and African drumming at the chapel.”

Joseph had a personal awakening at the Institute. He says he will now “be able to speak more for myself to tell my story and my experience.” Those things surely are different for someone, a missioner like Joseph, crossing the ocean to live in someone else’s land. “I have recovered my joy and realized that no one can take my joy since it comes from God.”

Cavine was perhaps surprised to learn that the cultural training at IBCS is not only for Black people. Attending were White religious from Jesuit and Josephite religious communities. The program also welcomes lay participants. “I was able to learn more about the Black church in terms of evangelization in a very inclusive way, says Cavine.”

“I see affecting my ministry in Glenmary missions in a very positive way, since I will be able to put into practice the skills I got from Black church preaching classes, evangelization, and catechetics classes.” He thinks his experience will positively affect him as he ministers in Glenmary areas.

Jude, a White Louisianan, found it all a bit challenging hearing “about whiteness and white privilege, about white nationalism, racism, white supremacy.” It struck him as a bit divisive, even one-sided, he says. “I will never consider myself a racist,” he insists. He was willing to share that point of view in the classes. “I was always taught that whatever, that you’ll, you’ll be whatever you, you believe and conceive, you can, you can achieve with hard work.” He talked about how many White people are in poverty, at society’s margins. “That’s the biggest group.” Reputable poverty statistics bear that out.

So he was often uncomfortable. On the other hand, he found the worship to be “beautiful, really. Lively. It’s just different. So I like it. But it’s not for everybody!

“I just want to live my life and just do well, do good,” he says. “Treat people fairly, love one another.” But he did learn some new things. “Leaving there, I found this class was enlightening, learning about the struggles.” At age 50 or so, he admits that he has taken “a blind eye. Even though I’ve lived, worked and breathed amongst Africans and African Americans, I’ve never asked any questions that were in depth and very personal.”

We all know that Black people are not all alike. Nobody is. But it’s always a temptation to group people together by the color of their skin or their place of origin. That cultural “tone-deafness” may be all the more surprising in the difference a Ugandan might have with a Black citizen of eastern North Carolina or southwest Georgia. Or for that matter, the way a White person might, in their mind, lump Kenyans and black Georgians into the same culture because of similar skin tone. It’s ridiculous when you think about it, but most people never consider it. These four missioners are less likely to fall into that, more likely to be effective in cross-cultural mission. That is what the program is all about.