Fifty years ago, Glenmary helped create a document on the Church in Appalachia. Bishop Stowe reflects on its relevance today. By John Feister

This year marks the 50th anniversary of a landmark document for the Church in Appalachia. But don’t count it out yet—This Land Is Home to Me: A Pastoral Letter on Powerlessness in Appalachia continues to influence the mission of the Church in this region.

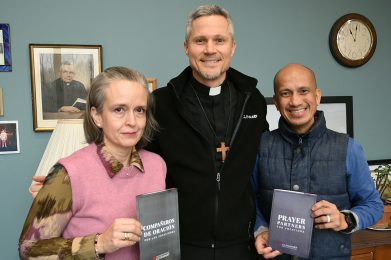

The document, issued in 1975, came from a synodal process. That is, it started with listening at the grassroots and having conversations to discern the local challenges for the Church. It was signed by all 25 Catholic bishops whose dioceses are partially or completely in Appalachia. Glenmarians were instrumental in its creation, working closely with others in the Catholic Committee of Appalachia (CCA), a federation of Catholics working in the region.

We asked Bishop John Stowe, bishop of the Diocese of Lexington, Kentucky, about the living significance of the pastoral letter. A Conventual Franciscan, he helps lead CCA as its episcopal moderator.

Q: Do you think the document is still relevant all these years later?

A: It’s very relevant. I’ve been rereading it this year and been talking about it quite a bit. I think it also has to be read in light of the two subsequent letters, one by the bishops 20 years later [At Home in the Web of Life], and then the so-called People’s Pastoral that came out in 2015.

I think there’s a progressive course within them. The third one [People’s Pastoral] really shows the influence of Pope Francis. It’s written by the laity, calling on the authority of the magisterium of the poor and the magisterium of the earth.

The first one [This Land is Home to Me] was really groundbreaking because, you know, it’s written in a very accessible style, kind of a free-verse poetry, looking at the land, the people, looking at the context, and the environment. Then looking at the way that the message of Jesus is to be incarnate there and then setting direction for the Church going forward. We were not familiar with Church documents written in such an accessible way.

Q: People have called Appalachia a colony, like an overseas colony. Most of your diocese is pretty much in Appalachia; what do you think about that statement?

A: In some ways it’s still true, but I think, more, we’re reaping the results of that because the coal mining industry is in a long period of bust, and we have a greater awareness of the damage that the coal industry does, not only to miners but to the environment.

On the one hand, you have people who are fiercely defensive of coal as something that provided their livelihood, and in some cases their identity as coal miners. But the very same people who would insist that we need to keep coal as an option don’t necessarily want their kids going into that work because they know the long-term consequences of breathing in the dust.

Q: As a bishop, how do you avoid the kind of polarized positions of: “We believe in coal” vs. “We think coal is the enemy”?

A: We always have to be respectful of people’s livelihoods and their culture. I think the key is listening to people’s stories, because when they hear themselves talk about the damage that it’s done to their health, the community, and the environment, they’re not quite as defensive about it. But if you come in attacking a way of life and that which has given them their identity, they’re going to be defensive. And it’s understandable.

Q: In some ways, the letters started naming the environmental crisis that was all tied up with this industry. It seems like Pope Francis had that same understanding of what was happening in his region.

A: Pope Francis was very good at connecting the human and the ecological issues, realizing that according to our faith, our economies are always supposed to work for the flourishing of the human person, not the person working for the economy.

At Home in the Web of Life kind of anticipated what Pope Francis does with Laudato Si’, making the interconnections. Most people will agree about the natural beauty of the Appalachian region. But oftentimes the majestic mountains, the waterfalls, the trees, can hide the poverty that exists side by side with them. The pastoral letters ask the question: Why is that? Pope Francis in Laudato Si’ recognized that the exploitation of the poor to fuel development in other places is a global phenomenon, that we’re all interconnected.

I believe Pope Leo is going to have his own style for sure, but he has spoken on several occasions in the short time that he has been in the papacy about the importance of the environment and the importance of care for creation.

Q: Pope Francis embraced a spirit of synodality, of listening and dialogue, which was certainly the spirit of This Land Is Home to Me. Will that spirit outlive Pope Francis?

A: I certainly hope so. Synodality requires not only conversion, but a changing of the Catholic culture. And that means it’s a lot harder than just implementing a program. I’m very hopeful about it. I think the Church needs it to survive. I think that was the vision of Pope Francis. In Pope Leo’s first English interview he pretty much was saying that synodality is about everyone having a voice and a say in the direction of the Church. You know, that requires a conversion.

You can read the three pastoral letters at ccappal.org

Partner with us in sharing God’s love where it’s needed most. Donate today.