At Holy Family Catholic Church in Macon County, Tenn., parishioners are remembered by having their names taped to the pews.

Just as everywhere, in rural America the coronavirus pandemic changed lives almost instantly. There the infection lagged behind urban centers, it’s true, and lower population density sometimes lessened or even hid the effects of COVID-19. Yet social distancing restrictions have included the rural regions since the beginning. Diocesan guidelines, too, limiting celebration of the sacraments, including the Eucharist, rites of initiation, and practically any church gathering have changed mission life deeply.

Missioners, though, will be missioners. We asked some of our Glenmarians for firsthand reports on just how they are coping with the pandemic. From drive-thru food pantries in South Georgia, to socially distant house calls in North Carolina, to online parish meetings and placing cameras in worship spaces for online Masses—even in the Tennessee mountains—Glenmarians have been creative as ever, reaching out to their communities.

Here are some of their stories.

Live-streaming in the missions

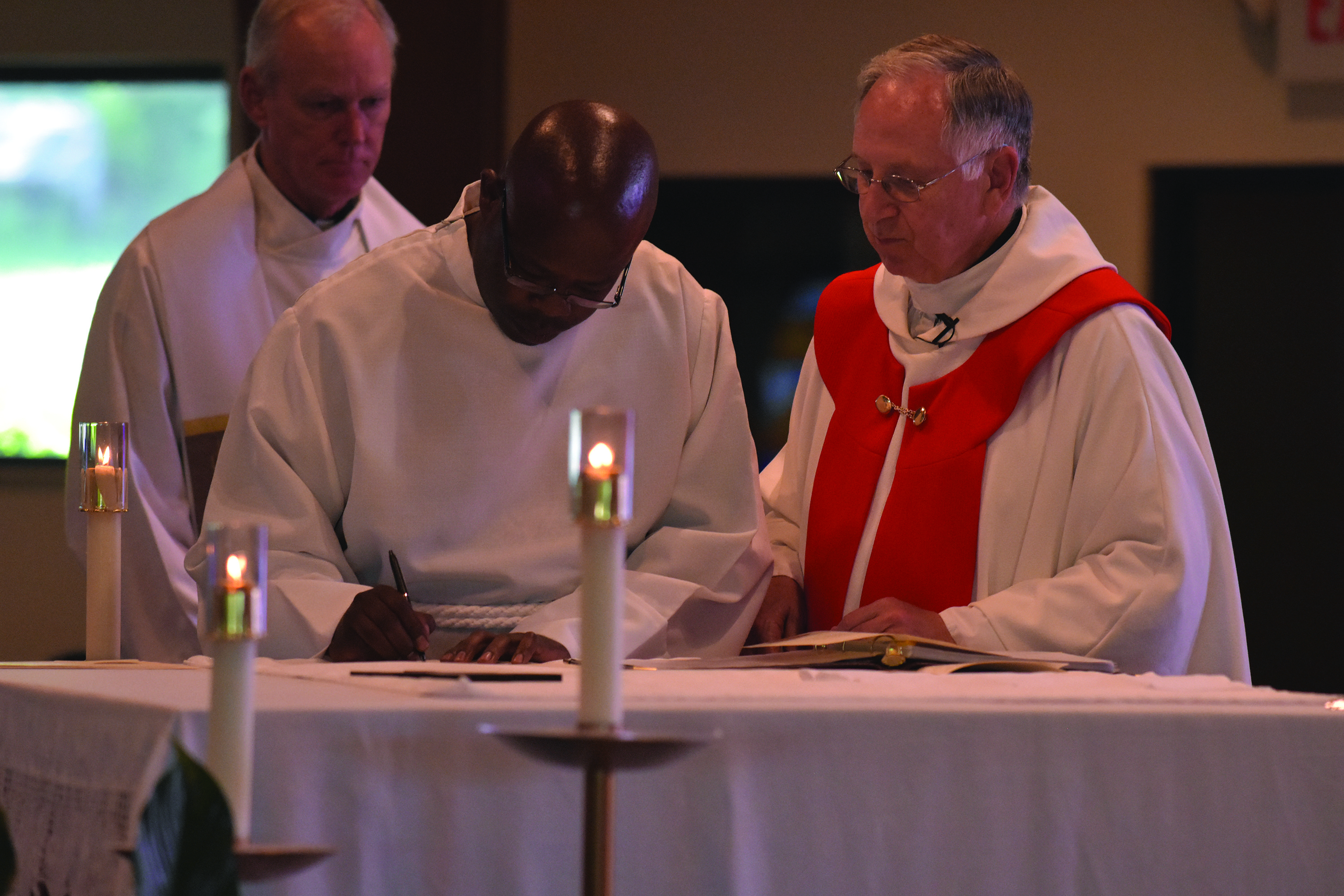

“We reach our parishioners by calling them,” says newly ordained Father Charles Aketch. He means all of them in Macon County, Tenn., served by Glenmary’s Holy Family parish. “We divide among ourselves who calls which families. This we do on a weekly basis.” They are working from a brand-new mission church—the first permanent Catholic church-building ever in that county, dedicated just last year.

Father Chet Artyciewicz was temporarily assigned to that same mission while pastor Father Vic Subb, having shepherded the church-construction project, took a few months to attend a seminary-based ministry enrichment program. (The pandemic brought him back to Tennessee early.)

In the pandemic’s earliest days, the ministry team considered a kind of drive-thru Holy Communion from the church parking lot. They ultimately settled on weekly live-streamed Masses (English and Spanish), like so many parishes worldwide.

It was something altogether different for a small parish in rural Tennessee to be on the internet for anyone in the world to watch! On Palm Sunday, though, palms were in the church parking lot for parishioners to pick up, one at a time.

“We help the poor buy food, pay rent, pay utilities, get some gas,” says Father Charles. “Most people have lost jobs and now they look upon the Church to come in and help them move on with life. Thanks to God our generous donors have sent us some resources, finances, to help meet the needs of the people we serve.”

Longing for Eucharist

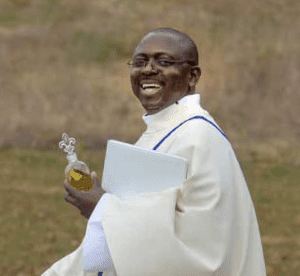

Father Richard Toboso, seen here as a deacon, served his first year as a priest at Holy Spirit mission in Bertie County, N.C.

Far out in the eastern end of North Carolina, also newly ordained Father Richard Toboso spends a lot of time making socially distant house calls. His parishioners “thirst for the truth,” as the Prayer for the Home Missions says. He celebrates Mass alone, but came up with an idea to get his parishioners more immediately involved.

“On the last Sunday in Lent, I devised a way to try another step. I shared with them that after I finished Mass by 9:45 a.m., I would do exposition of the Blessed Sacrament at the rectory chapel. (Here at Holy Spirit we do not have a church building of our own.) I asked them to stop by and receive Communion from 10 a.m. to noon, if they were feeling fine. But also I shared with them that they are not obligated.

“A number of them showed up and received Communion. They actually stayed for a few minutes before the Blessed Sacrament until the next person was at the front porch.”

Other than administering Communion, Father Richard, of course, kept his place praying well away from the parishioners. “One woman actually drove the half-hour alongside the Albemarle Sound, from the mission in Plymouth,” reports Father Richard. “She just celebrated her 80th birthday in February and she really misses Masses and Communion.”

Longing was a recurrent theme for the parishes in Bertie and Washington Counties. Father Richard reflects, “I have come to understand how much people long to receive the Eucharist.”

Then there’s food of a more practical type. Brothers Virgil Siefker and Curt Kedley had helped to organize an interfaith food pantry in Bertie County over the past few years. They figured out in the pandemic how to turn it into a drive-thru pantry. Brother Virgil reports that “one day we received 1,000 pounds of apples to give to people” and another day “we received 1,000 pounds of chicken from Perdue.”

At this writing, Brother Curt continues to work part time at the local nursing home, “as long as I pass the temperature test.” And he speaks of extending things in the food pantry: “A couple of us have targeted mostly shut-ins around town: 11 elderly folks that live at the old hospital and the Village Apartments. I delivered 14 boxes of food to them yesterday. I meet them on the front porch.” He also reports that Father Richard has been sharing daily reflections via Facebook.

Zooming in the Tennessee hills

Glenmary’s Kenn Wandera leads a “Food and Faith” fellowship session via Zoom meeting.

Kenneth Wandera’s deaconal ordination has been delayed and scaled down to a small gathering, but he is not deterred. He’s using Zoom, a free internet video-conferencing service, to convene the formerly in-person gathering at St. Michael the Archangel parish in Erwin, Tenn. “Usually people bring food, and they share faith stories together. That’s why we call it Food and Faith!’’ The isolation makes the food part impossible, but the faith-sharing continues. “Once people log in, we ask a very simple question: ‘How are you doing?’ We get the feel of where people are in their lives, and learn the struggles they and their families are going through.”

Father Neil Pezzulo helped gather food for those in need during the pandemic lockdown.

That same software is helping Glenmarians across the mountains from each other get together and share community. Father Neil Pezzulo set it all up and trained his brothers how to use it. “We had a family bring up food tonight!” says Father Tom Charters to the group online, “and another family yesterday. The best was the chocolate chip cookies!” You can practically hear lips smacking through the computer. More seriously, Father Tom reads some instructions from the Knoxville bishop, and there is chat about life in the parishes, remarkable support via a collection box set up outside the church—the nuts and bolts of running even a small parish.

In the land of cotton

There are many other mission stories that we could share here, but let’s end with southern Georgia. That’s where the pandemic hit hardest in the Glenmary missions. And Brother Levis Kuwa has paid the dearest price. A nurse, he fearlessly worked in the emergency room of the Southwest Georgia Regional Medical Center in Randolph County (a one-story, 105-bed hospital).

Brother Levis Kuwa contracted the coronavirus, but has since recovered and returned to work as an emergency room nurse in rural Georgia.

One day he awoke not feeling well, and soon tested positive for COVID-19. He took to bed in the St. Luke rectory in Randolph County near the hospital, while his partner in ministry Brother Jason Muhlenkamp quarantined himself in their home in Early County, 30 miles away. Pastor Father Mike Kerin gave up his place in Randolph County’s rectory, moving to the Early County rectory while tending to both of their needs.

Brother Levis was on the mend, but, about two weeks into the infection, he noticed a persistent soreness and weakness on his left side. At this writing he was in the hospital in Albany, itself a coronavirus “hotspot,” undergoing assessment. His good spirits remain, though, even in the hospital, unable to see visitors. “They know how to fix me,” he says, during a recent phone call from his hospital bed. He is, after all, a medical professional—and a man of faith. [Update: Brother Levis is at home again, still healing.]

Brother Jason came out of quarantine in good shape, and continues finding ways to support families in financial crises.

Whether serving spiritual or physical needs in their community, Glenmary is a dedicated bunch. As one Glenmarian reminds us, “Indeed we are in tough times, but God will not abandon us.”

This story first appeared in the Summer 2020 edition of Glenmary Challenge magazine.