“I’ve been dreaming of this day for 40 years!” That’s Glenmary Father Frank Ruff, excited to be part of breaking new ground in ecumenism. This past January the Glenmary Ecumenical Commission spent three days faith-sharing and praying with a group of ministers and members from the Churches of Christ at Abilene Christian University (ACU) in Abilene, Texas. “It was a moment of grace,” says Glenmary First Vice-President Father Aaron Wessman, who made the long trip to north-central Texas to participate. “This kind of a breakthrough with a community like the Churches of Christ is not a small thing.”

A scholar and minister from Churches of Christ echoes Father Aaron. Douglas A. Foster, who spent his career teaching Christian history at ACU, reflects, “When you’re talking about visible Christian unity, some people say, ‘Well, that will never happen.’ But it is a priority. If we take Jesus’ prayer for unity in John’s Gospel seriously, we can not do any less. These couple of days were absolutely successful.”

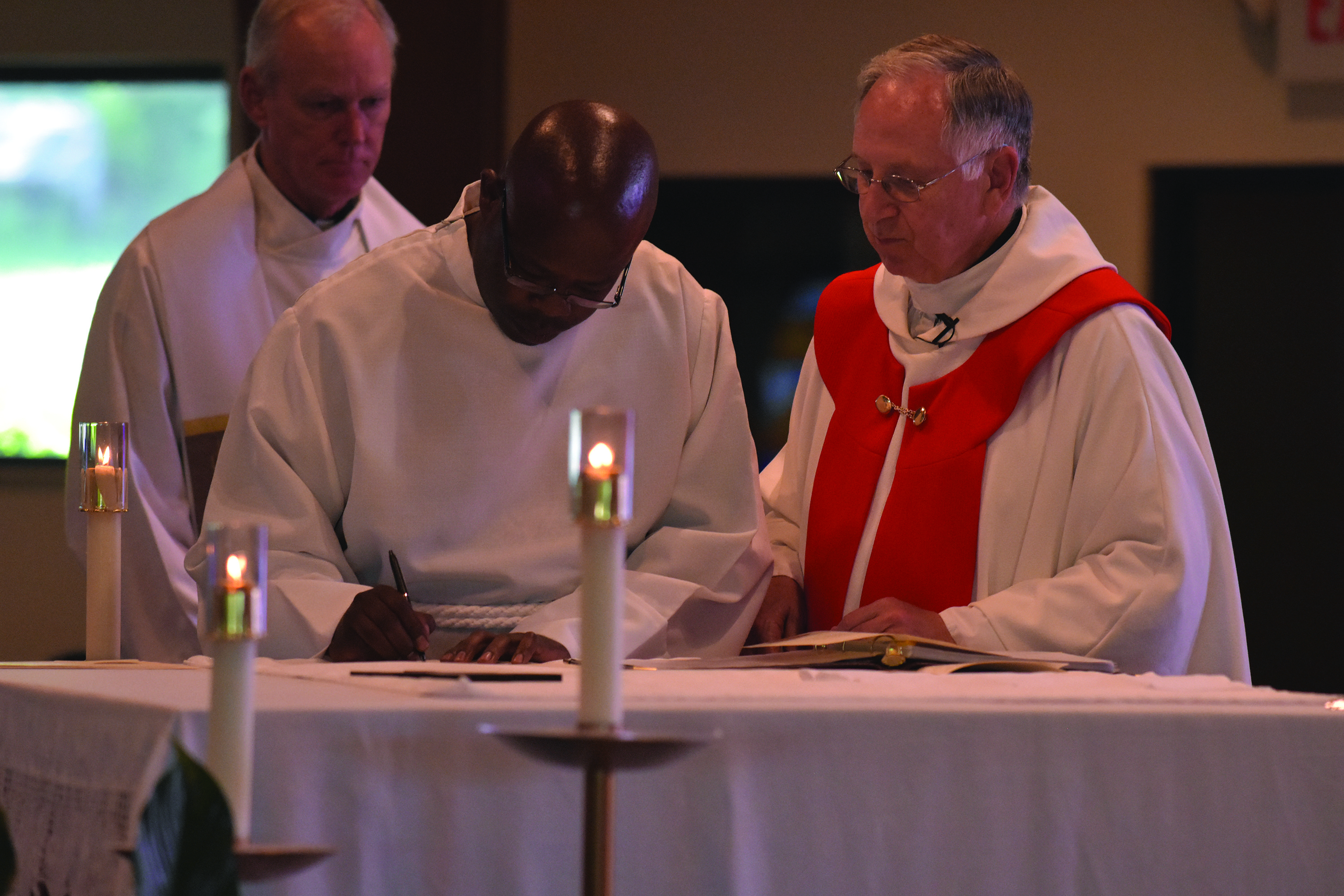

The meeting took place in the library amid ACU’s 4,000-student campus. Father Aaron describes it, from the Catholic side, as “an informal dialogue under the umbrella of the United States bishops.” Glenmary’s ecumenical work, particularly through its Ecumenical Commission, is in the name of the US Conference of Catholic Bishops.

A Movement for Unity

The Churches of Christ are part of a broader Protestant movement, the American Restoration Movement, which set out in the early 1800s to restore what it considered lost or neglected Christian practice and to build Christian unity. Two of its leaders, Presbyterian minister Barton W. Stone and the Presbyterian father and son Thomas and Alexander Campbell, came together in central Kentucky to practice “unity amidst diversity.” In what has become known as the Stone-Campbell movement, they sought for Christians to do the same in every community, in simple worship and service.

Each congregation in Churches of Christ maintains its independence, which remains one huge visible difference from Catholicism. Perhaps the other biggest difference from Catholicism is the movement’s reliance solely on the New Testament for its practice of Christianity.

Alas, this movement for Christian unity was unable to hold itself together. People of varying backgrounds couldn’t overcome differences of understanding about the nature of the Church and its mission, wrote Foster in “The Story of the Churches of Christ.” The heirs of the movement are three loose affiliations of congregations that are present worldwide today in the Churches of Christ, the Christian Churches and the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), including over six million members worldwide

Thirty universities the movement spawned include Pepperdine University, Lipscomb University, and, of course, ACU. Churches of Christ congregations are everywhere in the U.S., especially in the American South, but in every state and in 80 countries, especially in Africa and India.

“That all may be one”

The key to the three-day meeting was faith sharing, which may well be the most effective way for Christians to move past barriers of misunderstanding, even fear. The group of about 15 took turns over a day and a half sharing how Christian faith came to them and how it has shaped their lives. “You have to really make friends in order to get very far with trust and working together,” says Richard Roland, a Churches of Christ leader who works in Memphis, Tennessee. “These groups have been separated for a long time. And a lot of us really believe in Jesus’ prayer of John 17, “that all may be one.” That plays itself out in communities back home, says Douglas Foster: “If you in fact are really, truly creating friendships at a spiritual level, it can lead to conversations concerning faith. And if a person does not have faith, you can offer, through conversation and modeling, the life of a Christian, a follower of Christ.”

This type of sharing doesn’t come easily. Glenmary Father Frank Ruff, longtime ecumenist with the Southern Baptist Convention, recalls a relationship he had with a Churches of Christ minister back in Tennessee, where he was stationed to provide Catholic ministry to the people of the local county. “We met together every six weeks for a year, but could never have a relaxed faith sharing. We always ended disagreeing. I’ve always regretted that.” He dreamed of a day when that faith sharing could happen.

Father Ruff’s experience of fear or distance from the Churches of Christ minister would be typical. Just as Catholics a generation ago were discouraged from attending a Protestant worship service, or of marrying a Protestant believer, the Churches of Christ members today tend to be leery of Catholics. One of the ministers told the Glenmary Ecumenical Commission in Abilene, “If my congregation found out I was here, talking to Catholics, they might well dismiss me.” Old habits die hard.

Foundations of Fellowship

For all of the significant differences between Catholicism and the Churches of Christ, there is a world of similarity. Those things we share in common are the places to further our unity, says Keith Stanglin, a professor at a Churches of Christ seminary in Austin, Texas. For example, there is the language with which we talk about the Lord’s Supper, even though Catholics and Churches of Christ don’t see eye-to-eye. “I’ve encouraged people, including my students, and my church, to use biblical language about the Eucharist. Don’t get up there and say, ‘this symbolizes the body of Christ. Just say as scripture says; ‘This is the body.”

The Churches of Christ, unlike many Protestant denominations, celebrate Communion weekly. But would his church members treat the Body and Blood as Catholics do? “I’m comfortable with saying, yeah, this is the body and the blood. This is the presence of Christ. But I would say, ‘mediated through the Spirit.’ I would stop short of saying this is literal flesh and blood. But if we had that same language, it might be less offensive to Orthodox or Catholic folks.” Some members of his church, though, would be more comfortable with considering Communion more as symbolic than the real presence of Christ, he says.

At a Wednesday evening worship service, at a local congregation, the Commission was treated to a simple meal followed by a sample of four-part-harmony singing that is central to Churches of Christ worship—traditionally no musical instruments are permitted in church (no candles, incense or the like, either). We sang from the hymnbook created for Churches of Christ all over by ACU professor emeritus of music Dr. Jack Boyd, who led singing by a congregation who sang their parts well. The Catholics there agreed: It was inspiring.

Over a plate of Texas barbecue, at a roadside restaurant after the third daylong meeting, Foster reflected on an unexpectedly rich gathering: “I really think that there were seeds planted among some of our people in Churches of Christ. They’re going to actually be very intentional about looking for ways, simple ways, to be together, as Fr. Frank himself modeled. Go to dinner, lunch or breakfast with them, go to their worship services and become friends with people. Out of that can come real understanding.”

Plans are already in the works for follow-up using social media, and for having this kind of gathering with Southern Baptists and other denominations in the future. “I think it changed us,” says Father Aaron. “It certainly changed me. I was reminded of how important ecumenical dialogue is. If people of goodwill come together, it can change people in the body of Christ, and it can really make a difference for the Kingdom of God.” Father Frank Ruff’s 40-year dream is coming true.

— By John Feister